In a disastrous drought, a grim milestone: California could see its first big reservoir run dry

SF Chronicle

Kurtis Alexander

Nov. 12, 2021

REDWOOD VALLEY, Mendocino County — Lake Mendocino, once a plentiful reservoir nourishing the vines and villas of Sonoma and Mendocino counties, today is little more than a large pond, cowering beneath the coastal hills.

The exposed and cracked mud on the reservoir’s floor, as much as the wildfire that burned the grassy lake bed last summer, is the very portrait of drought. Few places in California have been hit as hard by the two-year dry spell as this sprawling stretch of Wine Country.

Tens of thousands of people who rely on the reservoir, between Healdsburg and the Ukiah Valley, in the upper Russian River watershed, have endured months of painful water restrictions. Households have been forced to cut back as much as 50%, while grape growers have sometimes gotten no water at all. The hardship may soon get worse.

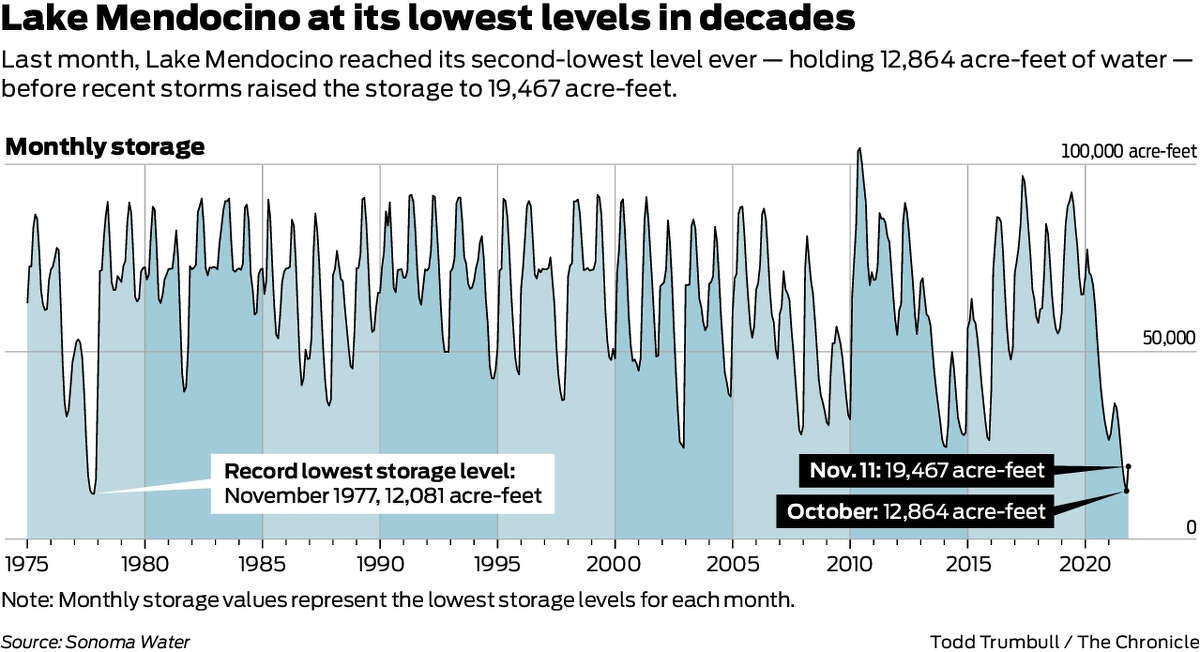

State officials warn that Lake Mendocino could be the first major reservoir in modern times to go dry. While rain over the past few weeks has lifted the lake above its October low, the reservoir, a few miles northeast of Ukiah, remains at less than 20% capacity. Officials worry that the looming wet winter season won’t bring enough inflow to meet next year’s water demands.

“This is a real concern, and one that we need to start looking at,” said Erik Ekdahl, a deputy director at the State Water Resources Control Board. “We really can’t have a scenario where a whole gigantic population runs out of water.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom visited Lake Mendocino in April to declare California’s first drought emergency. The water situation, the product not only of little rain but also of warm, dehydrating temperatures in the face of climate change, has just deteriorated since.

The region’s water managers recently learned that a nearby Pacific Gas and Electric hydroelectric plant that supplies about 30% of the reservoir’s water is offline for at least 18 months because of a faulty electric transformer. The out-of-service Potter Valley Project, which gets water from a neighboring watershed, will send only minimal flows to the lake in the meantime.

Should the reservoir dry up — once unthinkable — many of the basin’s cities and towns served by the lake or the upper Russian River, where the reservoir collects and releases its flows, have no significant backup.

“It’s not if we’ll be doing conservation measures next summer, it’s to what extent,” said Terry Crowley, utilities director for Healdsburg, which is already mandating that residents and businesses cut their water use 40% compared with a year ago.

Up a gravel driveway lined with Zinfandel vines in the community of Redwood Valley, the pinch of the water shortage is as tight as it gets.

Kevin Klotter, who retired from the Bay Area to the rural town north of Lake Mendocino, had been using rainwater collected on the roof of his workshop to shower in his yard — until it got too cold outside.

“I built a little surround for it, just rigged it up with excess lumber,” he explained, as he stood in his front lawn. “The water wasn’t heated, but in the middle of the summer, it was warm enough.”

Kevin and his wife, Bree, are among about 5,500 people in Redwood Valley who are limited to using 55 gallons of municipal water a day, among the strictest restrictions in Northern California. It’s about enough for two long indoor showers, without laundry, dishwashing or yard watering.

“It hasn’t been too difficult for us,” Bree Klotter said. “We got married in 1977, which is the year of a drought, and that informed our life together.”

The local water district enacted the caps after it lost its water supply from Lake Mendocino because there wasn’t enough to go around. The community, a mix of modest homes, horse ranches, cannabis grows and vineyards, is buying whatever water it can from the neighboring district. That district, like Healdsburg, Cloverdale, Hopland and so many others in the basin, is also getting less water from the lake and the river downstream, and having to ration as a result.

“I don’t think we’re going to have any water at all next year,” said Bree, who sits on the Redwood Valley County Water District board. “It’s scary.”

To prepare for an outage, Bree and Kevin are weighing whether to run a water line to their home from their irrigation well, which now serves their small plot of grapes.

Lake Mendocino, which can hold 122,400 acre-feet of water, had about 19,500 acre-feet of water in it last week. An acre-foot is enough for about two California households annually.

With the region needing at least 25,000 to 40,000 acre-feet of water to get through the dry summer and fall, another winter with little rain could leave reservoir storage short of what’s needed. This year, the lake emerged from winter with less than 10,000 acre-feet of new storage.

“You run the math out and see the concern,” said Ekdahl of the State Water Board. “The prospect of what a dry winter means — I don’t think people have wrapped their heads around that.”

Over the past two years, the watershed has received less than half its average annual rainfall, 14.8 inches and 13.5 inches in Ukiah between Oct. 1 and Sept. 30, respectively. The past summer also was one of the hottest.

Officials with the Sonoma County Water Agency, which manages the reservoir in concert with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, say the likelihood of another similarly dry year is low, based on what’s happened historically.

The problem, though, isn’t just the weather. PG&E’s disabled Potter Valley Project means less water coming into Lake Mendocino regardless of how much falls from the sky. Roughly 9,000 acre-feet is expected from the project this winter, about half of what’s typically sent, according to PG&E.

The hydroelectric facility normally operates by drawing water from the Eel River watershed to the north, to drive the turbines, and dispensing it in the east fork of the Russian River, where it flows to the lake. Until the powerhouse is fixed, which could be two years, PG&E doesn’t need the water, which leaves the company obliged to move only minimum amounts to the Russian River for fish and wildlife.

“This is going to make us incredibly dependent on seeing five or six more big (storm) events like we saw (last month),” said Don Seymour, principal engineer for Sonoma Water, referring to the 7 inches of rain that fell in Ukiah over a few days in October. “It puts a lot more pressure on Mother Nature.”

Sonoma Water and others vested in Lake Mendocino have requested that PG&E increase its water transfers. PG&E, though, may face legal and logistical constraints to doing so. It also could face opposition from some who want to keep more water in the Eel River.

“We are evaluating whether we have the ability to make discretionary diversions for non-generational purposes,” PG&E spokesperson Paul Moreno told The Chronicle in an email.

The water levels at the lake and in the river downstream are also affected by increased groundwater pumping. With the river and reservoir providing less water, people have been more reliant on wells, sometimes pumping water so close to the surface that they’re undercutting the creeks that feed the basin and the Russian River itself. Reservoir managers recognize the loss but don’t have an exact accounting of it.

Also, officials say current storage in the lake may be overstated. Since the reservoir’s construction in 1958, it has been slowly accumulating sediment on its floor. The volume of water that the reservoir holds today could be thousands of acre-feet less than what the gauges say it is.

Not far off Highway 101 amid the vineyard-covered hills, Redwood Valley Cellars, with its grand tasting room, custom crush facility and countless organic vines, has already been cut off entirely from the Redwood Valley County Water District’s diminished supply.

Since April, about 200 growers in Redwood Valley have been without district water. Hundreds of others in the basin who draw water directly from a waterway have been ordered by state regulators to stop pumping, fallout of the governor’s emergency drought declaration.

Martha Barra, whose family owns Redwood Valley Cellars and the labels Barra of Mendocino and Girasole Vineyards, has turned to pond water as well as some trucked-in supplies to irrigate. But between what little runoff has filled her ponds and the dry weather, she produced only about half the typical yield of her nine varietals this year.

Nearby grape growers have reported similar losses, generally between 20% and 60%, according to the Mendocino County Farm Bureau. Crop value in the watershed, which includes such prized wine spots as Alexander Valley and part of Dry Creek Valley, is estimated to be as much as a few hundred million dollars.

“The water just hasn’t gotten to the deep roots. It’s just not there to get the vines the vigor they need,” Barra said. “This is the worst we’ve ever seen it.”

To pay the bills, Barra hopes to collect crop insurance for the first time since her family took over Redwood Valley Cellars more than two decades ago.

The region’s water agencies, local communities and state officials have been meeting to figure out how to get by with little — or perhaps no — water in Lake Mendocino next year.

Foremost, they expect to put more restrictions in place, and restrictions starting earlier in the year, to reduce demand and preserve whatever water winter brings.

This year, the State Water Board began curbing water use in August, with the orders for growers, homeowners and even water agencies to stop directly drawing from waterways in the upper Russian River basin. Agencies providing for municipal use could still take a very small amount.

“It’s been a big crunch, but we’re lucky our community has really come together and supported what we’re doing,” said Jared Walker, who manages the Redwood Valley County Water District and a handful of other small public water agencies in the Ukiah area that have passed their restrictions along to residents. “I don’t anticipate myself lifting the 50% conservation notices for my customers at this point.”

Administrators of Lake Mendocino are also pushing ahead with a groundbreaking water management program to prop up reservoir levels. While most reservoirs face strict federal rules on when to make water releases for flood control, Sonoma Water and the Army Corps have been working with state, federal and university water experts to make such decisions based on new, more precise forecasting tools. They expect to be able to hold at least a little more water in the reservoir as a result.

Lake Mendocino’s fate has repercussions beyond the upper Russian River watershed — to more than 600,000 additional people in Sonoma and Marin counties.

While these communities have other sources of water, including Sonoma Water’s slightly larger and fuller Lake Sonoma, they have historically received some of their supply from Lake Mendocino. The nine retail suppliers that Sonoma Water serves also have put water restrictions in place. These include the cities of Santa Rosa, Petaluma and Rohnert Park, as well as the Marin County Municipal Water District.

“I’m worried,” said Seymour, with Sonoma Water. “Maybe if you’re a gambling man, you’d bet against it (Lake Mendocino running dry). But, unfortunately, we’re caring for the water supply for hundreds of thousands of people. That represents a risk we’re simply uncomfortable with.

“Until we see big (storm) events start to occur and the system start to recover,” he said, “I’ll remain concerned.”

Recent Comments